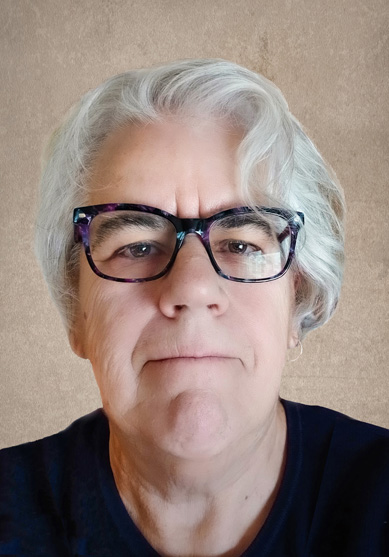

Goldie Award-winning author Patricia Spencer writes novels for sapphic romance readers who want it all: Mature women. Slow burn. Angst. And abiding love.

I love romances but rarely find complex stories featuring older women, so I decided to write their tales myself.

My novels straddle the romance genre and women’s fiction. They centre mature women in an unfolding love relationship. My main characters have histories, live complex lives, and offer insights into issues of core identity and how we interact with each other and the world.

My books go beyond the central romantic relationship to layer in different aspects of love, asking: How do we extend it beyond our lovers to include family, friends, and even strangers? How do we meet life with love?

Here’s my promise: Although I put my women through hell, they always – always – get their happy ending.

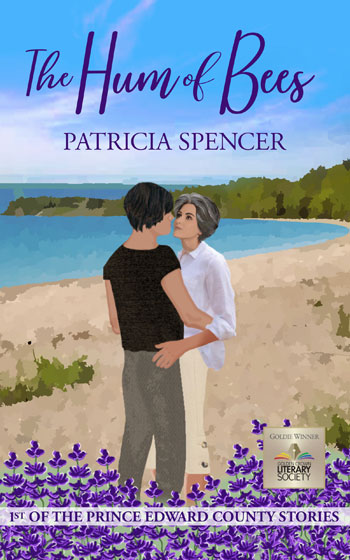

Click an image below to see more about each book.